Veterans often face adjustments when they return home

By James Grob, jgrob@charlescitypress.com

An unknown author once wrote, “A soldier doesn’t fight because he hates what is in front of him. A soldier fights because he loves what he left behind.”

It’s an honest and bittersweet sentiment, to be sure, but unfortunately, the things a soldier leaves behind are not the always same when he returns.

And more often than not, the soldier himself is not the same, either.

Re-adjustment and re-integration to life back home can be a daunting task for many veterans of war, and the society at large doesn’t always understand the difficulties.

Often, even the closest friends and family members of veterans aren’t able to comprehend what a veteran returning home might be going through.

Master Sergeant David Minton of Milo, now retired after 28 years of service in the U.S. Air Force, was deployed to numerous locations throughout his career as an aircraft maintenance technician and an aircraft quality assurance inspector.

He said he would rather not discuss if he ever served in a combat zone, and he’d rather not say if he personally has ever experienced any symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

That’s not unusual. There is a long tradition of veterans not wanting to discuss details of what they’d seen and done with anyone besides other veterans. Even with other veterans, the more serious subjects are often avoided.

“They may or may not have (experienced symptoms),” said Minton, who is married with two adult children. “We talk about the good times.”

PTSD is a mental health problem that some people develop after experiencing a life-threatening event, like combat, a natural disaster, a car accident or sexual assault. After a trauma or life-threatening event it is common to have reactions such as upsetting memories of the event, increased jumpiness or trouble sleeping.

Seven to 8 percent of the general population will experience PTSD at some point in their lives, but that number rises rapidly for veterans. It is estimated that between 11 percent and 20 percent of veterans who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom will experience PTSD.

About 12 percent of veterans who served in Operation Desert Storm have experienced or will experience PTSD. About 30 percent of Vietnam War veterans have experienced PTSD at some point in their lifetime.

Veterans groups list “combat stressors” — things soldiers experience that make them more likely to be inflicted with PTSD, such as seeing dead bodies, being shot at, being attacked or ambushed, receiving rocket or mortar fire, or knowing someone who was killed or seriously injured.

PTSD symptoms usually start soon after the traumatic event, but for some people, they may not happen until months or years after the trauma. Symptoms may come and go over many years.

Many veterans with mental illness symptoms do not come in for services. Minton believes some may not understand how serious the illness is.

“Everyone handles stress in many different ways. They may not realize there’s a problem,” he said.

Mental illness professionals urge veterans to keep track of symptoms and talk to someone they trust about them. If symptoms last longer than four weeks, cause great distress or disrupt work or home life, a vet should seek professional help from a doctor or counselor.

According to the most recent report in 2016 published by the Veterans Administration, which analyzed 55 million veterans’ records from 1979 to 2014, an average of 20 veterans a day die from suicide — more than double the suicide rate of the general public.

Thoughts of suicide and depression are often related to mental illnesses such as PTSD.

Many veterans, however, do not seek help. Experts say there are many reasons for this — concerns about being seen as weak, being treated differently, concerns about privacy and that others might lose confidence in them. Some don’t believe mental health treatment is effective.

“Trust is a thing,” said one U.S. Marine Corps vet, retired from the military and living and working in northern Iowa, who asked that his name not be used. (For the purposes of this article, he will be referred to as John.)

“I think a lot of younger veterans don’t trust mental health doctors the way they might trust a physician to fix a broken bone or treat physical symptoms when they’re sick,” John said. “Mental illness just seems different than physical illness.”

He said that there also could be problems with access to mental health care. Veterans might have to travel a good distance to receive care, and the costs might be prohibitive.

John, who is married and has one young child, did serve in a combat zone, but like Minton, he did not want to talk about combat specifically. He said he did experience combat stressors and has seen symptoms of PTSD in himself, but he’s seen more serious symptoms in some of his friends who served.

“A lot of people will say that loud noises like a car backfire or fireworks will trigger some kind of flashback,” John said. “I’ve never had sounds bother me, but I’ve had smells trigger me. Like the sulphur smell of gunpowder will make me feel a lot of anxiety, or a wet, moldy smell in the basement will remind me of that same smell when I was serving.”

Minton is a member of both the American Legion and the Veterans Administration, but advises his fellow vets to discuss whatever anxieties they have with their loved ones first.

“Family first. Talk. Listen. It takes a while to adjust to anything new,” Minton said. “Stay positive and find what works well for you. Keep an open mind.”

John agreed with Minton. “It’s hard for anyone to adjust. If you have family you can confide in, talk to them,” he said. “Talk with other veterans who will understand.”

For many service members, being away from home for long periods can cause problems at home or work, and these problems can add to the stress. This may be even more so for National Guard and Reserve troops who had not expected to be away for so long. Almost half of those who have served in the current wars have been Guard and reservists.

Sometimes when veterans return to civilian life they have trouble finding work. Many feel like their service is counted against them when they apply for a job. The skill set learned in the military is seen as somehow different from the set of skills learned at a university or a community college.

“I was lucky. I found a shipping company that was hiring managers, and they were specifically encouraging veterans to apply,” John said. “My time in the military allowed me to afford a college education. I have no complaints, personally.”

John did mention that some of the people he served with have told him they believe they have been passed over for jobs because of their service.

“Some of my friends say they feel discriminated against,” he said.

Minton, who is enjoying retired life, said he feels he got the most out of his time in the service, and serving hasn’t held him back.

“My military aircraft maintenance experience allowed me to do something I truly enjoyed and pursue my Federal Airframe and Powerplant (A&P) certification,” he said.

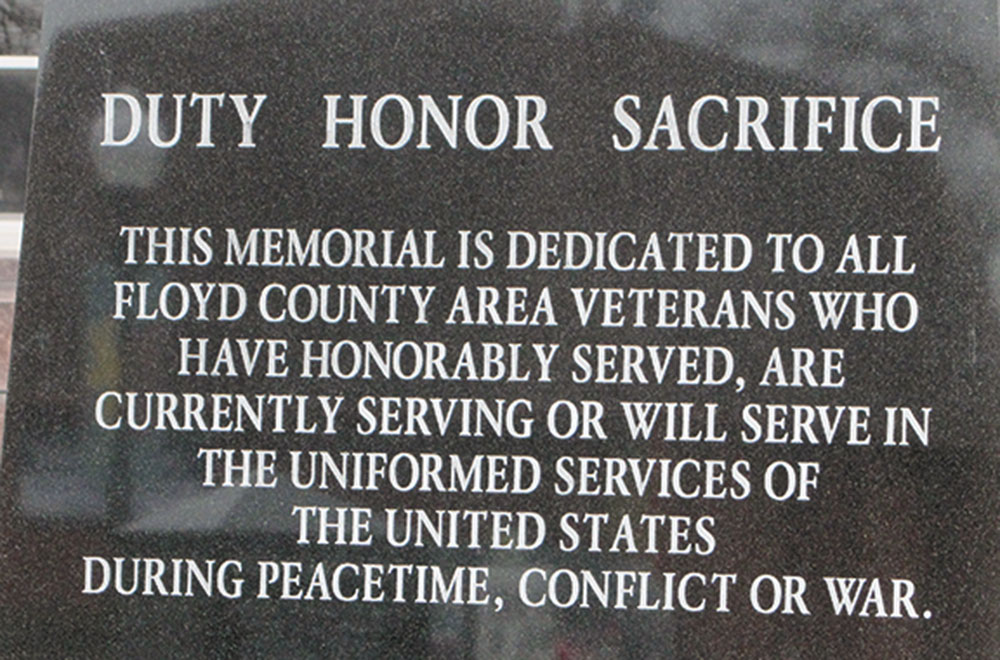

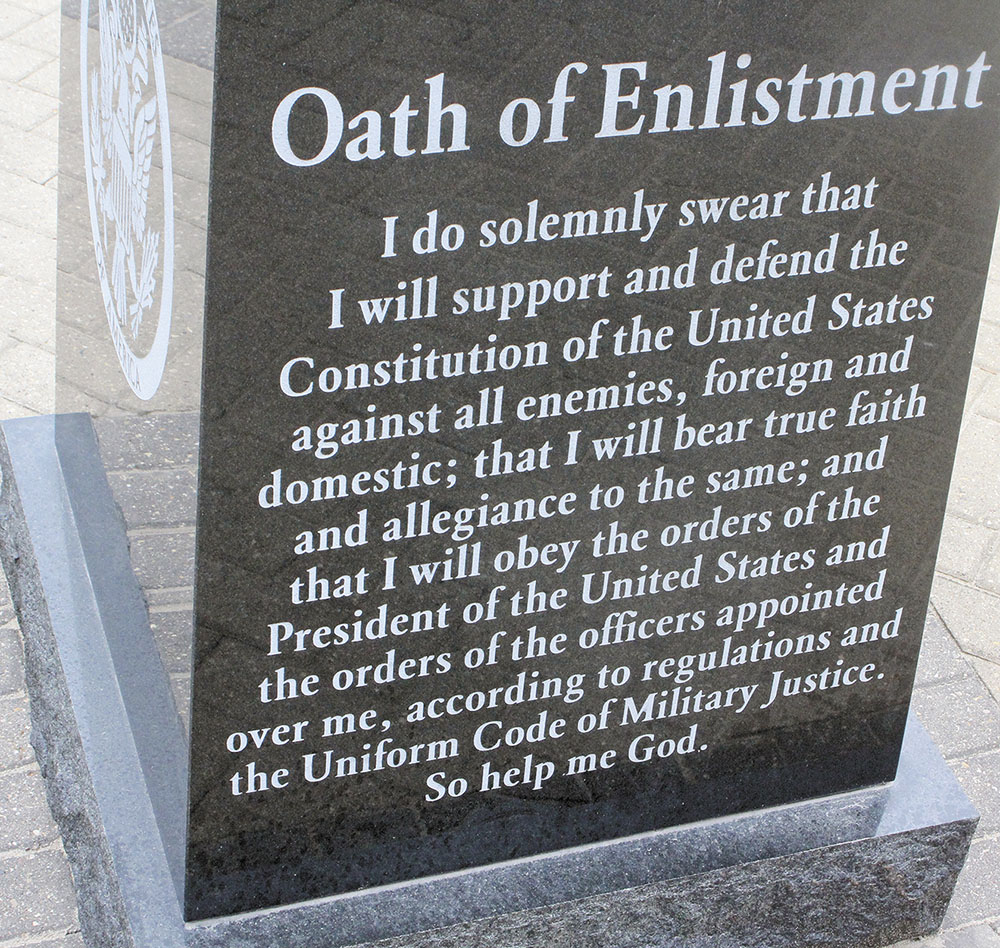

Minton said that those who haven’t served don’t completely understand the “service before self” life he lived for some 27 years, and they can never completely understand “the sacrifices our service men and women have given for their freedoms.” He believes it is important that Americans “show respect to our nation’s flag, and the national anthem, when played.”

If John had one thing he could tell the general public, it’s “don’t assume all veterans are the same.”

“I kind of get irritated when I hear someone in the media, or some politician say ‘veterans think this’ or ‘veterans believe that,’” he said. “There are a lot of veterans, and they’re a very diverse group, and I guarantee you they don’t agree on everything. You ask five different veterans what they think about something, you might get five different opinions.

“The one thing we all do have in common is we all sacrificed to serve our country,” he added. “Thank us for that, but don’t treat us as if we’re all alike.”

Social Share