Navigator carbon pipeline project offers information to Floyd County landowners

By Bob Steenson, bsteenson@charlescitypress.com

About 80 people attended a meeting this week for a chance to get information about and offer their opinions on the second carbon dioxide pipeline project proposed to go through Floyd County.

Other than the Navigator Heartland Greenway pipeline company representatives themselves, the only person who spoke in support of the project was the manager of the local Valero ethanol plant, which would be one of the users of the pipeline.

“We’ve been in business for 15 years in this area,” said Valero Renewables Charles City plant manager Chad Buffington.

“We partner with many area farmers, many of you in this room, along with the elevators in the area. We buy millions (of bushels) of grain every year from folks. We service thousands of tons of feed put back on Iowa farms,” he said.

“I will say we are investigating and looking at every option we can to lower our carbon intensity score. A project like this is going to be very beneficial going forward and keeping those relationships and businesses going,” Buffington said.

Other comments regarding the pipeline proposal covered a wide range of concerns, but many of those who spoke up questioned the need for the project, its impact on farmland and how landowners would be compensated – including the use of eminent domain to force easements on those who don’t want them.

The Iowa Utilities Board (IUB) hosted the meeting Monday afternoon, along with representatives of Navigator Heartland Greenway LLC, at the Youth Enrichment Center at the county fairgrounds.

It was the second-to-the last of 36 legally required public meetings, one in each Iowa county the pipeline route is proposed to pass through. The final public meeting was held Monday night in Butler County. An additional meeting online had been held the week before.

The proposal is for a 1,300-mile pipeline to transport liquid carbon dioxide, captured and compressed at ethanol and fertilizer plants in Iowa, Minnesota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Illinois, to deep underground permanent storage in Illinois.

The project includes 885 miles of pipeline in Iowa, with 13.99 miles of that proposed for Floyd County.

An attorney for the IUB told the audience several times during the event that nothing said at the meeting would be part of the official record that the IUB would use in its decision whether or not to grant a permit for the project, and whether or not to grant the right of eminent domain.

Because the decision of the utilities board is subject to court review, all comments and information that the board bases its decision on must be in writing, according to Iowa Code, the attorney said.

“Please, please, please, take part in the process,” he said, urging people to go to the IUB website – iub.iowa.gov – and file their comments under the docket for the Navigator project.

“I want landowner participation, because that is the only way your voices will be heard. Please, please participate. File in the docket,” he said.

A public meeting had to take place in a county before Navigator could legally talk with landowners in that county about easements. With all the public meetings now having been held, the company can officially apply for a liquid hazardous materials pipeline permit from the IUB, which the company said it will likely do this spring.

It can also request the authority to use eminent domain if it wants to use that to acquire land where the landowners won’t voluntarily agree to an easement. Asking for that power would trigger another public hearing process, the IUB attorney said.

Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, vice president for government and public affairs for Navigator, told the group about the company’s proposal, stressing the desire to work with landowners to come up with voluntary easement agreements.

She said Heartland Greenway would potentially transport up to 15 million metric tons of CO2 per year from up to 20 ethanol and fertilizer processors, including eight Valero ethanol plants — including the one near Charles City — and the Iowa Fertilizer Co.

Navigator’s involvement would be providing the transportation, she said. The producer of the carbon dioxide would continue to own it, and be eligible for federal carbon sequestration tax credits set to increase to $50 per ton or possibly higher.

Ethanol and fertilizer plants produce some of the purest quality carbon dioxide as part of their production processes, Burns-Thompson said, making them uniquely suited to carbon capture and storage efforts.

In addition to carbon storage tax credits, the companies can use carbon capture and storage to lower their carbon index, making them eligible to sell their products in states or countries that set carbon limits or penalties, or to sell them at a premium price.

Navigator has established a potential half-mile wide corridor for the route for the pipeline through the state, saying it won’t know specifically where within that half mile is best for the 50-foot-wide easement for the pipeline until it has a chance to talk with landowners and complete surveys.

Stephen Lee, Navigator executive vice president for engineering, said if a permit is granted by the Iowa Utilities Board, construction could begin on the $1.6 billion project in early 2024. It could begin bringing some of the ethanol and fertilizer facilities online by the end of 2024 and finish in 2025, he said.

Based on their comments, many of the people who spoke at the meeting hope that day never comes.

Others, however, implied the project would be OK if landowners thought they were being treated fairly, suggesting that an ongoing lease agreement such as wind farms use would be preferred to a one-time easement payment.

But the difference between this project and wind farms, Burns-Thompson said, is that wind farms take the land for the turbine and access roads out of production and so a farmer can no longer plant that area.

The intent of the pipeline project is to restore any land disrupted for the project to the condition it was previously, meaning a farmer can continue using that land for crop production.

Monica Howard, senior director of environmental and regulatory for Navigator, said farmers would be compensated for 100% of the value of the crop on land affected the first year, 80% the second year and 60% the third year, in addition to the easement payment. Those damage payments would come even if there was less or no crop damage those years, she said.

Landowners would continue to be covered for project-related crop loss in the future if it extended beyond that 240% original total, she said, and they would be covered for any damages in the future if the company needed to do maintenance or repairs on their property.

Many of the people who spoke were concerned about the ability of Navigator surveyors to go on private property without permission as long as they give 10 days written notice, and the ability to force easements through eminent domain.

The IUB attorney said that Iowa Code, passed by elected legislators, establishes the right to survey with written notice, and eminent domain has not been approved yet, nor had it even been requested yet.

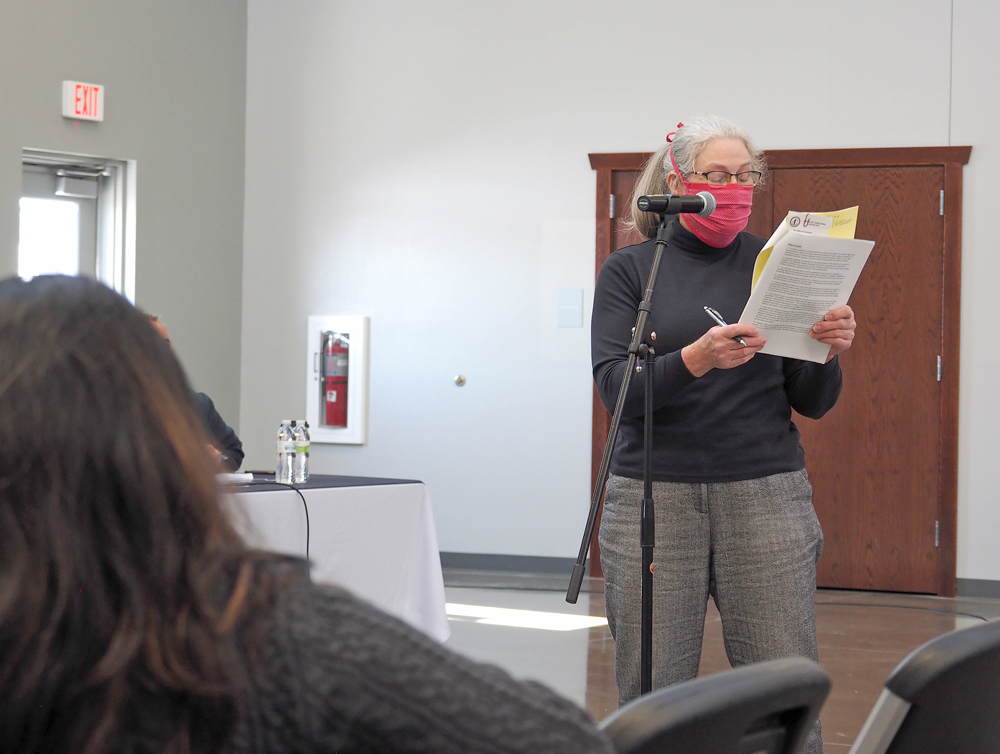

The Navigator spokespersons said several times they want to work with landowners collaboratively and reach mutually agreeable easement contracts, but one woman responded, “If it was truly collaborative, eminent domain wouldn’t be needed.”

Some of the more than 20 people who spoke in the question-and-answer session brought up safety concerns.

One man said a 10% concentration of CO2 can cause people to lose consciousness, and he accused the Navigator representatives of not worrying about safety because “it’s in my backyard, not yours.”

Lee acknowledged that even a 6% level of CO2 is considered toxic, so one of the first things they do is analyze potential dispersion if there would be a rupture and locate the pipeline so that it’s “hundreds and hundreds of feet” from inhabited areas.

They also strategically locate valves that shut immediately if sensors see a change in pressure or flow, so only a limited amount of CO2 can escape even if there is a rupture.

The type of steel to be used in the pipeline and design of the system “greatly exceeds all those regulations,” Lee said, plus the company conducts ongoing risk assessments.

One woman asked if it wouldn’t be better to store the CO2 where it is produced and transport it to storage facilities by truck, but Lee said pipelines have been proven the safest method of transport when compared to truck, railroad or other means.

The attorney from the IUB started the meeting by giving information about the permitting process in Iowa for hazardous liquid pipeline applications, the rights of landowners affected by the pipeline’s path, requirements for land restoration after the project is finished, and the law on payment for damages and inspections during the construction process.

“As landowners, you have the right to ask Navigator to address your concerns. You also have the right to ask for changes in the route and changes in easement agreements. The negotiation process is the time to request such changes and to address any concerns you might have,” the attorney said.

“It is usually helpful to be specific with your requests and your concerns, so the company can work with you.”

Then Navigator’s people gave an overview of the company, the project, how carbon capture and storage (CCS) works, economic and environmental impact, and finally how landowners would be compensated for being involved.

Those first two parts of the presentation took just under an hour, then the meeting was opened up to the audience and more than 20 of the people there spent the next almost two hours asking questions and making statements.

The Navigator meeting was the second public meeting held by a company interested in building part of a carbon capture and storage pipeline in Floyd County. The first, by Summit Carbon Solutions, had been held in September in Floyd.

Social Share